Pyramid schemes, including notorious forms like the Airplane Game and illegal outfits such as the Blessing Loom, often entice individuals with the alluring promise of rapid financial gain, yet they invariably collapse, leaving participants in a state of financial disarray.

This article delves into the intricate dynamics that drive these schemes, examining their economic framework, recruitment hurdles, and psychological influences. It makes a clear distinction between pyramid schemes and Ponzi schemes, while also highlighting their affiliations with multi-level marketing and chain referral schemes. Furthermore, it scrutinizes notable instances of collapse, such as the 1997 Albanian civil unrest and the 2016 Vemma settlement, that serve as cautionary tales.

By grasping these critical elements, readers are equipped to uncover valuable lessons that can shield them from encountering similar traps in the future.

Key Takeaways:

Why Most Pyramid Schemes Fail: The Economics Behind the Collapse

Pyramid schemes are intricately designed as fraudulent systems, or investment frauds, that allure participants with the promise of high returns derived from the investments of new recruits, creating an illusion of profitability. However, the inherent instability of these schemes leads to their inevitable downfall, as they depend predominantly on the perpetual recruitment of new members, lacking any genuine investments or legitimate products.

This paper investigates the economic dynamics underpinning pyramid schemes, examining their exploitation of financial crises and the broader financial sector, including informal markets and deposit-taking companies, while elucidating the reasons behind their ultimate failure to fulfill their extravagant claims.

Definition of Pyramid Schemes

A pyramid scheme represents a sophisticated form of investment fraud, fundamentally predicated on the recruitment of new members. Participants are lured with the promise of high returns, which are derived not from any legitimate product or service, but solely from their ability to recruit additional individuals.

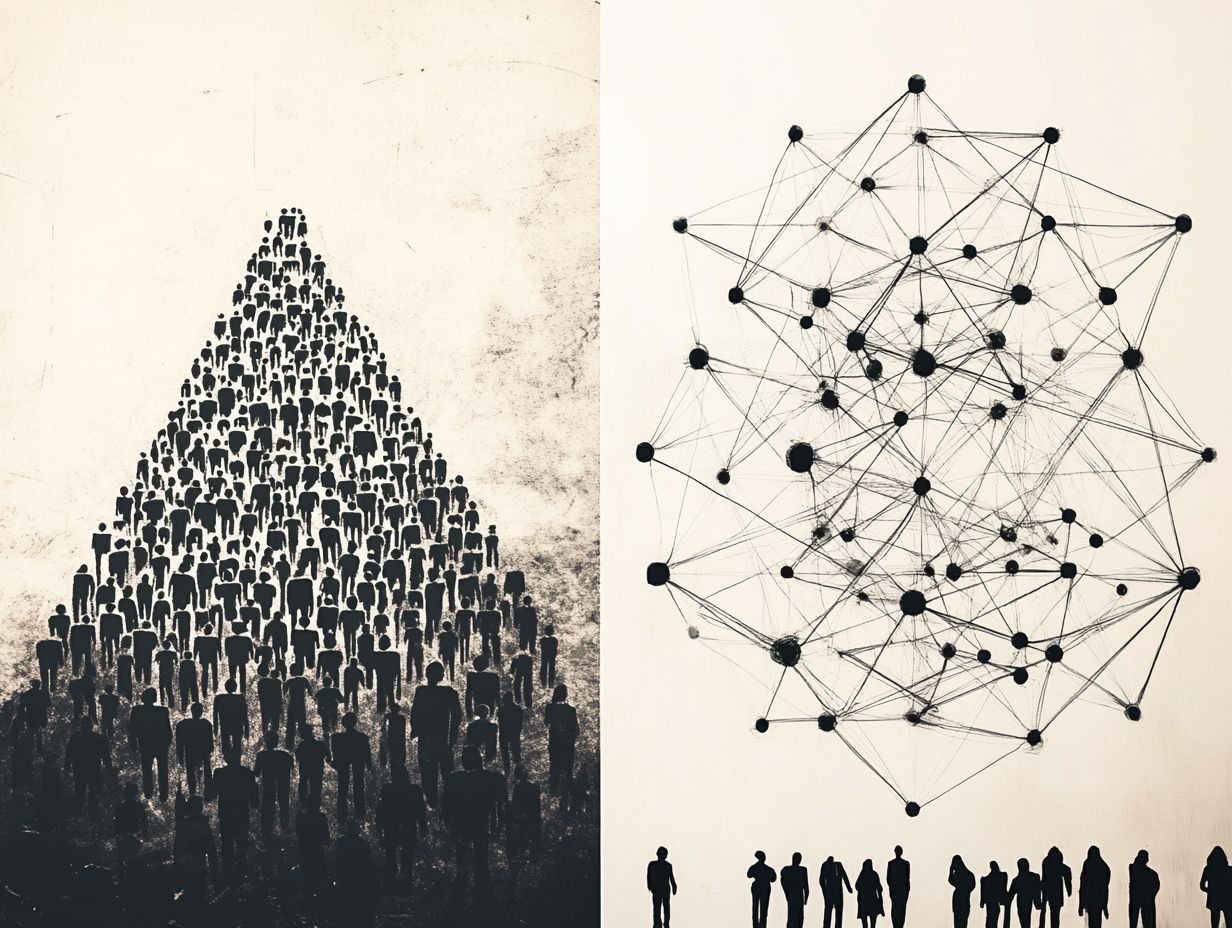

The structure of these schemes mirrors a pyramid, with the initial promoters positioned at the apex reaping the most substantial rewards, frequently at the detriment of those who join later and may struggle to recruit enough new members to realize any returns, often resulting in participants losing money.

In stark contrast to legitimate multi-level marketing practices, which emphasize the sale of tangible products and offer commissions for both retail sales and recruitment, pyramid schemes lack viable goods, existing primarily to perpetuate the earnings of their top-level participants. This illicit operation often employs aggressive recruitment tactics, obscuring the inherent risks for newcomers and ultimately leading many to experience significant financial losses, reminiscent of marketing fraud.

Overview of Pyramid Scheme Dynamics

Pyramid schemes function on a model where the base layer of participants finances the upper tiers, engendering a cycle of exponential growth that proves unsustainable over time, much like illegal pyramid schemes found in Internet-based scams.

This arrangement cultivates a deceptive perception of profitability, as newcomers are often seduced by the allure of considerable financial rewards. Cash flows predominantly from these fresh recruits into the pockets of earlier participants, leading to a depletion of resources, as the structure relies heavily on a constant influx of new members, often characterized by recruiting others into the system.

Ultimately, when the stream of new participants begins to wane, the entire system collapses, leaving the majority with substantial losses and contributing to significant social consequences.

This dynamic not only illustrates the inherent risks involved but also underscores the ethical implications of exploiting hope and trust for financial advantage.

The Structure and Economics of Pyramid Schemes

The architecture of pyramid schemes is meticulously crafted to optimize recruitment while minimizing costs for the organizers, artfully concealing their fraudulent essence beneath a facade of legitimate business operations, similar to recruitment-focused businesses and marketing fraud.

Basic Models of Pyramid Schemes

Basic models of pyramid schemes exhibit variation, yet they frequently encompass multi-level marketing frameworks and selling franchises that prioritize recruitment over genuine sales of products or services.

In these schemes, individuals are typically encouraged to enlist new members, establishing a tiered system where earnings predominantly stem from the fees paid by recruits rather than from legitimate product transactions. This emphasis on recruitment can lead participants to invest substantial sums upfront, lured by the promise of high returns that seldom materialize, depicting a classic investment con.

Unlike legitimate enterprises, which generate revenue through the sale of goods or services to consumers, pyramid schemes are heavily dependent on a continual influx of new recruits to maintain profitability, often leading to an illegal massive money reception. For more insights on this topic, check out Why Most Pyramid Schemes Fail: The Economics Behind the Collapse.

The structured payment systems inherent in these models create a façade of profitability, ultimately leaving the majority of participants at a financial disadvantage while a select few at the top amass significant wealth, benefiting from high payouts and huge commissions.

Revenue Generation and Distribution

Revenue generation in pyramid schemes predominantly relies on cash flow from new recruits, with existing members typically receiving payouts based on the recruitment of others rather than the sale of legitimate products. This structure establishes a cycle where the income of those at the top is profoundly dependent on the continuous influx of new participants, rendering it a high-risk investment for the majority, often described as a fraudulent system.

Misleading advertising claims often herald the potential for substantial earnings, fostering an illusion of legitimacy that conceals the true nature of these schemes. As funds trickle downward, early participants may indeed receive cash rewards, but this ultimately comes at the cost of new recruits, who are enticed by alluring promises of effortless wealth, echoing the tactics seen in consumer protection cases.

Consequently, the entire operation hinges on an ever-expanding pool of recruits to uphold the façade of profitability and sustainability, often blurring the lines between legitimate products and marketing fraud.

Costs Associated with Participation

Engaging in a pyramid scheme typically entails considerable initial investments and continuous subscription fees, which can result in significant financial loss for participants as the scheme inevitably collapses, highlighting significant social consequences.

The initial buy-in often ranges from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, presenting a formidable barrier for many individuals. Following this upfront cost, participants frequently find themselves encumbered by recurring fees or the relentless pressure to recruit others to offset their own expenses, reflecting the unsustainable nature of such schemes.

This unyielding cycle can swiftly deplete their savings and may even lead to accumulating debt. In their quest to recoup their investment, the tantalizing promise of profit often remains frustratingly out of reach, leaving them to contend with profound financial repercussions that extend beyond mere monetary loss, adversely affecting their overall economic stability and mental well-being, often during times of economic emergency.

Reasons for Collapse

The eventual downfall of pyramid schemes can be attributed to various interrelated factors, including the illegal status of their operations. Market saturation plays a significant role, as the allure of new recruits diminishes over time.

Additionally, legal challenges increasingly pose threats to their sustainability, further complicating their operation. As the participant base dwindles, the capacity to attract new members becomes severely restricted, hastening the inevitable collapse of these schemes, signaling their return to the informal market.

Market Saturation and Recruitment Limits

Market saturation emerges as a pivotal factor contributing to the decline of pyramid schemes, as the pool of potential recruits dwindles, leaving the base struggling to sustain cash flow.

This saturation instigates a ripple effect, complicating efforts to attract new participants who might initially be enticed by the allure of rapid wealth but ultimately confront a harsh reality of disillusionment. As the number of available recruits diminishes, those already entrenched in the scheme often find themselves isolated, resulting in alarmingly high dropout rates, a characteristic of economic emergencies.

Consumer confusion frequently ensues, with various schemes cloaking themselves in different names, obscuring the distinction between legitimate business opportunities and deceptive practices. Consumers often confuse these schemes with legitimate multi-level marketing, further complicating their understanding. The inherent lack of transparency in these schemes exacerbates the challenges, rendering it difficult for individuals to accurately assess their true viability, while many remain misled into believing that success is still within their grasp.

Legal Challenges and Regulatory Scrutiny

Legal challenges and regulatory scrutiny are pivotal in the dismantling of pyramid schemes, with authorities such as the United States Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Bureau of Investigation actively engaged in eliminating these illicit operations. Regulatory frameworks have been established to protect consumers and maintain economic stability.

These initiatives frequently entail thorough investigations and enforcement actions aimed at safeguarding consumers who may fall victim to deceptive practices. Regulatory bodies meticulously examine business models, focusing on payment structures and recruitment tactics to pinpoint the warning signs typically linked to these schemes.

A multitude of states has enacted their own regulations, further complicating the already intricate legal landscape. Individuals found participating in or promoting these fraudulent setups often face significant legal repercussions, underscoring the inherent risks of non-compliance.

As public awareness increases, the regulatory framework continues to adapt, making it progressively more challenging for such operations to flourish in an environment characterized by legal vigilance.

Psychological Factors Influencing Participation

Psychological factors play a crucial role in shaping individuals’ decisions to engage in pyramid schemes, often blinding them to the inherent risks and fostering a belief in unrealistic returns. These schemes, sometimes disguised as chain referral schemes or gift circles, exploit human emotions. For more information, you can read about the reasons behind these schemes’ failures in Why Most Pyramid Schemes Fail: The Economics Behind the Collapse.

“`

This phenomenon can be traced to several underlying motivations, including a desire for rapid financial gain, social pressures exerted by peers, and a yearning for community and validation. Participants frequently find themselves captivated by the allure of substantial profits and the promise of effortless wealth, all while dismissing credible warnings regarding investment scams and consumer protection.

As they become increasingly entrenched in these schemes, cognitive dissonance may begin to take hold, complicating their ability to recognize red flags. Ultimately, this clouded judgment can lead individuals to disregard sound financial advice and make choices they would typically avoid.

Pyramid Schemes vs. Ponzi Schemes

Both pyramid schemes and Ponzi schemes represent distinct varieties of investment fraud, yet they differ fundamentally in their structural mechanisms.

Pyramid schemes primarily hinge on recruitment, incentivizing participants to enlist new members to generate profit. In contrast, Ponzi schemes allure investors by promising returns derived from the contributions of existing investors, creating an illusion of profitability without legitimate investment activities.

Key Differences and Similarities

The key distinctions between pyramid schemes and Ponzi schemes lie in their methods of generating income: the former primarily relies on recruiting others, while the latter utilizes the funds of existing investors to pay returns.

In pyramid schemes, individuals primarily earn money through the recruitment of new participants, establishing a hierarchy where income is derived from the fees paid by newcomers. This model is inherently precarious, often collapsing when recruitment efforts wane, resulting in substantial losses for those positioned at the base.

“`html

In contrast, Ponzi schemes lure investors with promises of high returns, relying on contributions from newer investors to pay earlier ones, rather than generating profits through legitimate business activities. For a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanics, check out this article on Why Most Pyramid Schemes Fail: The Economics Behind the Collapse.

“`

Both schemes share a deceptive quality in their marketing, often enticing individuals with extravagant promises while concealing their fundamentally risky and unsustainable structures. Recognizing these differences give the power tos individuals to navigate the financial landscape more effectively and avoid potential pitfalls.

Connection to Multi-Level Marketing

The relationship between multi-level marketing and pyramid schemes is intricate, with certain MLM structures displaying traits reminiscent of pyramid schemes, especially when they place a greater emphasis on recruitment rather than the sale of genuine products.

Legitimate vs. Illegitimate Practices

Legitimate multi-level marketing (MLM) practices stand apart from pyramid schemes primarily due to their emphasis on product sales, whereas pyramid schemes often obscure their true nature with convoluted marketing tactics. This distinction holds significant importance for potential participants exploring opportunities within the realm of direct sales.

In a genuine MLM model, individuals earn commissions based on the sales of products to consumers, fostering a business structure that promotes both personal financial growth and consumer satisfaction. Conversely, pyramid schemes prioritize recruitment over actual product sales, establishing a system where earnings hinge largely on the influx of new members rather than genuine sales transactions.

This fundamental difference brings about serious legal implications, as pyramid schemes are frequently classified as illegal. Consequently, consumers often find themselves bewildered, struggling to navigate the murky waters between these two business models.

Notable Cases and Examples

The prominent cases of pyramid schemes, such as Vemma Nutrition Company and WinCapita, serve as stark reminders of the destructive consequences of marketing fraud, highlighting not only the financial fallout but also the serious legal ramifications faced by those entangled in such schemes.

Consequences for Participants and Leaders

The consequences of engaging in a pyramid scheme can be profoundly detrimental, often culminating in financial devastation for many individuals and significant legal repercussions for the leaders orchestrating these illicit enterprises.

For those ensnared in these schemes, the immediate aftermath frequently entails considerable monetary losses, as the required investments can siphon off savings and disrupt personal finances. Meanwhile, those at the helm face the looming threat of serious criminal charges, accompanied by a tarnished reputation that may adversely affect their future business ventures.

Beyond the financial implications, the social ramifications are equally significant; victims often struggle with feelings of guilt and shame, which can strain relationships with friends and family who may also bear the brunt of the fallout. In the long run, both participants and leaders may find their careers impeded, with much of their credibility irreparably compromised, severely undermining their prospects for building a stable financial future.

Lessons Learned and Future Implications

The lessons gleaned from the collapse of pyramid schemes offer invaluable insights into the necessity for robust consumer protection measures and highlight the critical role of financial institutions in averting future economic crises.

These findings emphasize the pressing need for lawmakers to establish stricter regulations governing financial marketing practices and the promotion of investment opportunities. Ongoing consumer education initiatives become critical in equipping individuals with the knowledge required to differentiate between legitimate investment prospects and fraudulent schemes. By cultivating an informed consumer base, financial institutions can assume a pivotal role in safeguarding the economy against similar threats.

Ultimately, the responsibility extends beyond regulatory bodies; community organizations and educators must also engage in promoting awareness and empower individuals to make prudent financial decisions. The United States Federal Trade Commission plays a pivotal role in regulating investment cons and safeguarding consumers. For more insights, read about Why Most Pyramid Schemes Fail: The Economics Behind the Collapse.

“`

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a pyramid scheme and why do they always seem to fail?

A pyramid scheme is a fraudulent business model that relies on recruiting an ever-increasing number of participants to sustain itself. Eventually, the scheme collapses due to a lack of new recruits, leaving the majority of participants with significant financial losses.

Why do pyramid schemes collapse despite promising high returns?

Pyramid schemes cannot sustain themselves because they rely on an endless chain of recruits and do not have a legitimate source of income. As the pool of potential recruits dries up, the scheme can no longer generate enough revenue to pay the promised returns to existing participants.

What is the role of economics in the failure of pyramid schemes?

Economics plays a central role in the collapse of pyramid schemes. The model relies on a constant influx of new participants to generate profits, but as the pool of potential recruits decreases, the pyramid inevitably collapses.

Can pyramid schemes be sustained if they have a large initial base of participants?

No, even if a pyramid scheme has a large initial base of participants, it is still ultimately doomed to fail. The business model itself is inherently flawed and unsustainable, making it only a matter of time before it collapses.

What are some warning signs of a potential pyramid scheme?

Pyramid schemes, often confused with legitimate multi-level marketing ventures, can have devastating effects on consumers. Advertising claims of high payouts often lure individuals into making substantial initial investments. These schemes may also disguise themselves as subscription services or educational themes, adding to the confusion.

Some red flags of a pyramid scheme include a heavy emphasis on recruiting new members, promises of high returns with little to no effort, a lack of legitimate products or services being offered, and a recruitment-focused business structure that resembles chain referral schemes.

Can anyone make money in a pyramid scheme?

It is important to note that pyramid schemes are illegal in many jurisdictions, including the United States, where bodies like the United States Federal Trade Commission actively investigate such fraudulent systems. The financial ecosystem can be severely impacted by these schemes, causing social consequences and economic emergencies.

While it is possible for a small number of early participants to make money in a pyramid scheme, the vast majority of participants will lose money. This is due to the unsustainable nature of the business model and the inevitable collapse of the scheme. Additionally, the structured payment system often relies on cash from recruits, which creates financial instability.